Statement of Erin McCann

Before Subcommittee on Economic Development, Public Buildings, and Emergency Management

Union Station: A Comprehensive Hearing on the Private Management, the Public Space, and the Intermodal Uses Present and Future

July 22, 2008

Chairwoman Norton, members of the subcommittee, I’d like to thank you for the opportunity to speak to you today. I have a short statement, and then I’ll be happy to answer your questions.

My name is Erin McCann and I am an amateur photographer. I am also an active member of a group called DC Photo Rights, which exists to document and discuss incidents in which photographers have been harassed by security officers or police. These officers often mistakenly believe that taking pictures in public places is illegal, or requires a permit, or is an indication that the person holding the camera is somehow a threat.

I’ve never been clear on why, exactly, a camera is considered threatening. In the aftermath of the 2005 transit bombings in London, for instance, officials appealed to the public for snapshots taken before and after the attacks in their search for clues. An open photography policy can be a security team’s best friend. It also liberates security employees from the task of investigating people like me as I take photographs in the most obvious way possible. With a 10-inch lens on my camera, there is no disguising what I am doing.

In Washington, certain places have the reputation of being unfriendly to photographers. In the four years that I’ve been shooting in the city, Union Station has always been one of those places. In February, I began a series of phone calls and e-mails to Amtrak and Jones Lang LaSalle management to find out why.

I’ve included with my written statement a timeline of my involvement and my frustrating search for answers. Often, my calls and e-mails have resulted in being given conflicting information, sometimes minutes apart by people in the same office. The statement also includes details of some of the incidents in which photographers have been harassed, told incorrect policies by misinformed station officials, and, in certain instances, been threatened with arrest for daring to take a simple snapshot of a national treasure.

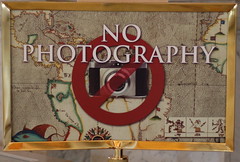

In almost every incident, a guard or officer has wrongly told a photographer that Union Station is private property and photography is not allowed. The reasons given for this fake policy vary. I was once told that my camera is “too professional.” Others have been told that the Patriot Act bans photography in train stations, a law that I’m sure would come as a surprise to the organizers of the annual Amtrak station photography contest.

I have been stopped twice in the last three months while photographing in the public areas of Union Station. Both were after I received explicit assurances from Amtrak and Jones Lang LaSalle management that photography is allowed. The most recent incident was last Friday, when an Amtrak employee—who refused to tell me her name—said the building was private property and that all photography is prohibited.

For many tourists, Union Station is a first stop and first impression of the nation’s captial. For a family to be warned or even threatened upon arrival simply for taking photos of one of the city’s beautiful public places is reprehensible.

My interest now is the same as it was in February when I first started asking questions:

1) To understand what the photography policy is at Union Station.

2) To assure that if there are restrictions on photography that they are clearly posted throughout the building.

3) To make sure those restrictions are fair, given the station’s unique ownership and its role as a major gateway for thousands of the city’s visitors each year.

4) And, finally and most importantly, I want to be sure that the private guards, Amtrak police and everyone else in a position to interact with the public understand what the policy is. Despite repeated assurances from the management of Amtrak and Jones Lang LaSalle, ill-informed station employees are still taking it upon themselves to interpret the policy as they see fit or to make up contradictory policies. Amtrak and Jones Lang LaSalle have so far been unable to communicate this policy to their security employees. I believe Washington D.C.’s train station deserves smart, well-trained, high-quality security, and my experience with its representatives so far has been exceedingly disappointing.

Curious about how other cities and stations handle photography, it took me 30 seconds on Google to come up with the policy at Grand Central Terminal in New York City. They post it right there on their Web site, and they welcome photographers with open arms. It’s taken over six months and dozens of conversations—not to mention a congressional hearing—to understand the photo policy at Union Station. And still we have no guarantee that when new guards or officers are hired, they, too, won’t automatically assume that a camera is a threat.

My hope is that after today, visitors to Union Station will be free to explore and photograph the building without being viewed as law-breakers. Security officers and Amtrak employees should have more important things to investigate than a tourist with a camera.

Thank you.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

3 comments:

Wonderful. We're heading in a dangerous direction, excellent to see people such as yourself trying to fix things. Thank you.

You mention Grand Central - the irony in all of this is that Grand Central IS private property that has been leased to a government agency as opposed to Union Station which is public property that has been leased to a private managment firm. Yet GCT recognizes its special role as a major tourist attraction and acts accordingly. Go figure.

Wonderful testimony. Personally, I think the issue isn't just a matter of cryptic and erratically enforced photo policy. The station is public property, and as such, constitutional rights come into play. There are certain restrictions that the station's management can not impose on the space, no matter how plainly stated or evenly enforced.

Post a Comment